27 January 2005

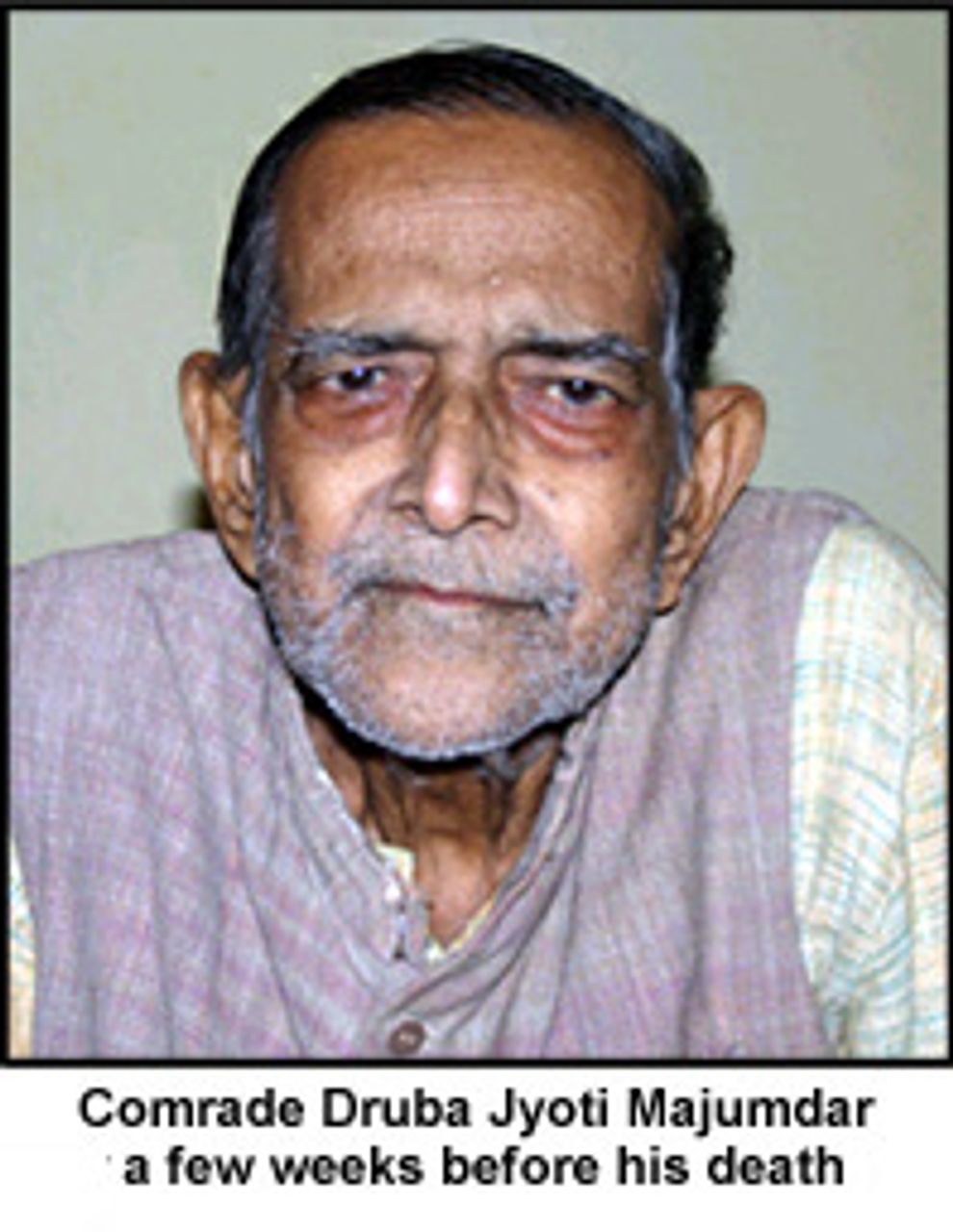

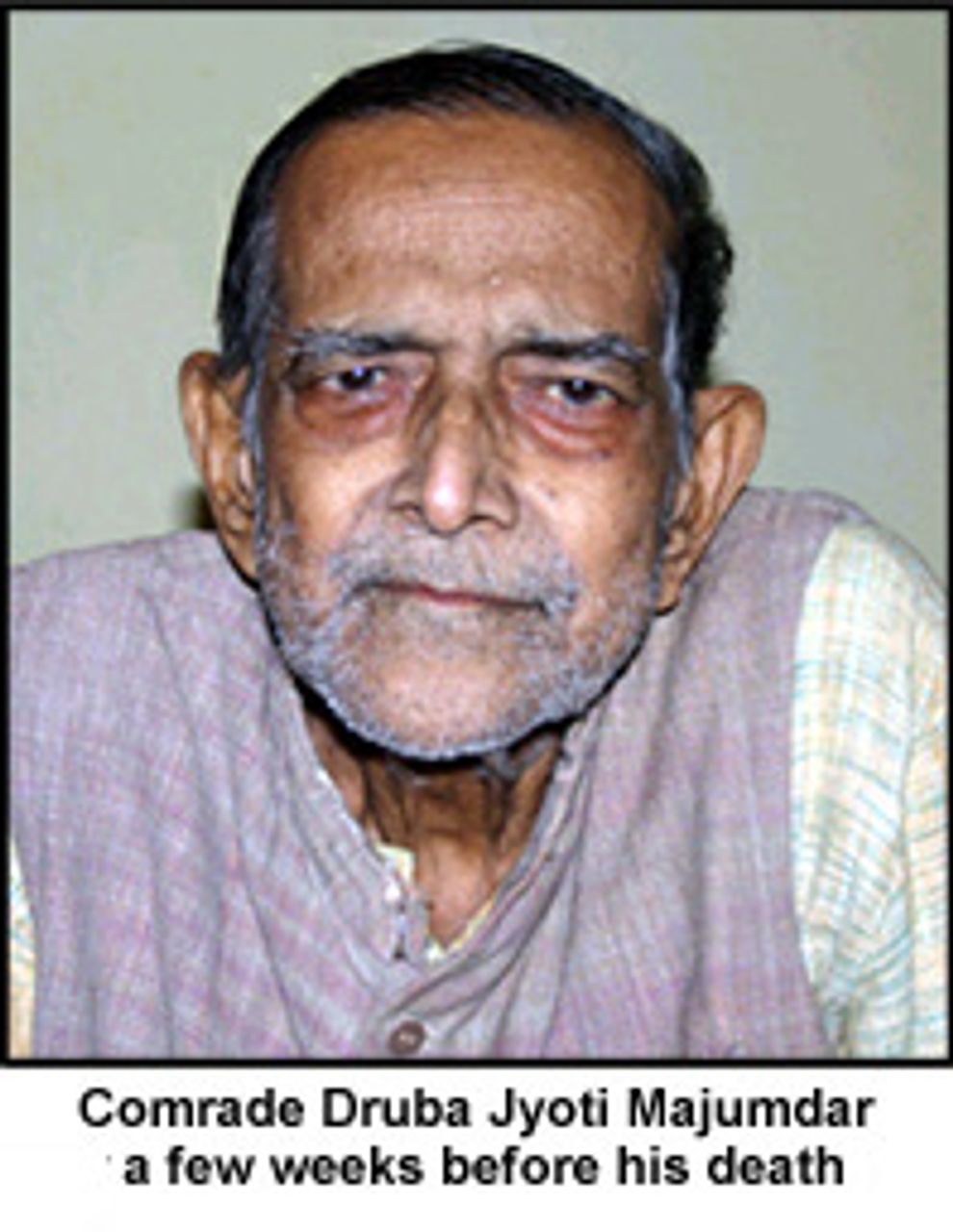

On the morning of Sunday, January 16, pioneer Indian Trotskyist Druba Jyoti Majumdar died at his home in Katwa, West Bengal, of asthma. He was 75.

Majumdar, who was known to his family and comrades as Durbo, joined the Bolshevik-Leninist Party of India (BLPI), the then section of the Fourth International in the Indian subcontinent, in 1946 at the age of 17. Throughout the remainder of his life he considered himself a revolutionary socialist and Trotskyist. But Durbo’s political development was cut off for decades by the dissolution of the BLPI’s Indian unit into the petty bourgeois Congress Socialist Party in 1948.

Not

until the early 1990s did Durbo and a group of Kolkata (Calcutta)

socialists with whom he was associated—most of them BLPI veterans—learn

of the decades-long struggle that the International Committee of the

Fourth International (ICFI) had waged against Pabloism, a virulent

opportunist tendency that arose within the Fourth International under

the pressure of the post-World War II restabilization of capitalism. Led

by Michel Pablo and Ernest Mandel, this tendency claimed that objective

forces would compel the Soviet Stalinist bureaucracy, its satellite

parties, the social-democrats, and, in the countries oppressed by

imperialism, the national bourgeoisie, to play a progressive and even

revolutionary role. The task of Trotsykists, therefore, was not to wrest

the leadership of the working class from these alien class forces, but

to pressure them to the left.

Not

until the early 1990s did Durbo and a group of Kolkata (Calcutta)

socialists with whom he was associated—most of them BLPI veterans—learn

of the decades-long struggle that the International Committee of the

Fourth International (ICFI) had waged against Pabloism, a virulent

opportunist tendency that arose within the Fourth International under

the pressure of the post-World War II restabilization of capitalism. Led

by Michel Pablo and Ernest Mandel, this tendency claimed that objective

forces would compel the Soviet Stalinist bureaucracy, its satellite

parties, the social-democrats, and, in the countries oppressed by

imperialism, the national bourgeoisie, to play a progressive and even

revolutionary role. The task of Trotsykists, therefore, was not to wrest

the leadership of the working class from these alien class forces, but

to pressure them to the left.

The ICFI’s critique of Pabloism shed an entirely new light on the BLPI’s dissolution—for which Pablo had pressed—and on the bitter political experiences that the members of the Kolkata group had subsequently made as supporters of the Pabloites’ international organization, now known as the United Secretariat. After extensive discussions with ICFI representatives, the Calcutta group, including Durbo, Dulal Bose, Ganesh Dutta, Nirmal Samajpathi and Dinesh Sanyal, joined the Socialist Labour League, the Indian organization in political solidarity with the ICFI.

Alongside Dulal Bose, Durbo henceforth played a leading role in developing the SLL’s work in West Bengal, the principal bastion of the Stalinist Communist Party of India (Marxist). Although hobbled by asthma, he wrote extensively for the SLL’s Bengali newspaper Anthrajathik Shramik (International Worker) and its predecessor Shramiker Path (Workers’ Path), addressed public meetings of the SLL in Katwa and Kolkata, made many Bengali translations of articles published on the World Socialist Web Site, and collaborated in preparing the Bengali-language edition of David North’s The Heritage We Defend: A Contribution to the History of the Fourth International.

A philosophy professor at Katwa College, Durbo had a keen mind and wide-ranging intellectual interests. He had studied the Marxist classics and both ancient and modern Indian philosophy. Fluent in Bengali, Hindi and English, he was an amateur philologist. When comrades visited from other parts of India or abroad he would delight in discussing and discovering the relations between words in different languages, including links between Sinhalese and Bengali.

Durbo made an exhaustive study of psychology and sought to illuminate psychological problems from a materialist perspective in the Bengali journal Manabman (Human Mind) and a two-volume work published in 2003-04, Manabik Chetanar Sawrup Sandhane (In Search of Human Consciousness). The West Bengal government has published his pioneering English-Bengali dictionary of Abnormal Psychology and Psychopathology.

Till the end of his days Durbo retained a boyish spirit. Although his asthma made it very difficult for him to travel, he was ever eager to contribute to the work of the Socialist Labour League. His concern for his fellow comrades’ health and well-being was testament to his generous spirit and to his understanding of the demands placed on, and the vital importance of, revolutionary cadres.

Durbo and the BLPI

Durbo was born on March 3, 1929 in Bapna, in the Rangpur district of present day Bangladesh. The second of five children, he came from a privileged Brahmin family. His father was a Deputy Magistrate entrusted with doling out British imperialist justice.

Under the influence of India’s mass anti-imperialist movement, the mounting struggles of the working class, and the horrors of fascism, world war, and the British-provoked Bengal Famine of 1943-44, Durbo rebelled against his upbringing. At the age of thirteen he participated in the Quit India movement, the spontaneous nationwide rebellion that erupted after the August 1942 arrest of senior Congress leaders.

Around this time Durbo cut off his “holy” thread, the symbol of a male Brahmin’s religious observance and caste superiority. Later he would defy the Indian tradition of arranged marriages.

Durbo first came into contact with the BLPI in 1947 in Calcutta, where he was studying economics at Presidency College. The two years between the end of World War II and the dissolution of Britain’s Indian empire were filled with momentous struggles of an incipient revolutionary character, including strikes, peasant rebellions, anti-feudal movements in the princely states, and mass demonstrations against the incarceration of members of Subhas Chandra Bose’s Indian National Army. Although India and Bengal were to be partitioned along communal lines in August 1947, these struggles invariably united Hindus, Muslims, Sikhs and Christians.

Durbo, as a result of his reading and study of events, had by this point already decided to become a Marxist. He well recognized the bourgeois character of the Indian National Congress. Under Gandhi’s leadership, the Congress mounted controlled mass mobilizations in order to pressure India’s colonial overlords to relinquish control over the state apparatus, while adamantly opposing any independent action of the working class or challenge to capitalist property.

Durbo had also taken the measure of the Stalinist Communist Party of India. In the name of defending the Soviet Union, the CPI had openly allied itself with the British colonial regime from the beginning of 1942 through the end of World War II, and it condemned and agitated against the Quit India uprising. During the semi-insurrectionary struggles of 1945-47, the CPI subordinated the working class to the rival parties of the national bourgeoisie, calling on workers to press the Congress and the Muslim League—whose leaders had daggers drawn against each other—to recognize their “responsibility” to combine and lead an anti-British National Front.

For a time in the mid-1940s, Durbo considered himself a follower of the Congress Socialist Party (CSP), which had played a leading role in the Quit India rebellion. A faction of the Congress, the CSP sought to combine Gandhianism with Fabianism and Marxism. By 1947, Durbo had grown troubled by the CSP’s acquiescence before the Congress leaders’ drive for a settlement with British imperialism, under which the Congress would take control of the colonial state machine.

Against the Congress, the radical nationalists of the CSP, and the Stalinists, the BLPI alone advanced a revolutionary perspective.

Founded in 1942 on the initiative of the Lanka Sama Samaja Party of Ceylon (Sri Lanka), the BLPI united Trotskyists in all parts of British and princely India and Ceylon.

The development of a pan-Indian revolutionary working class party was a strategy flowing from the LSSP’s adherence to the Fourth International and attempt to develop the program of permanent revolution. The tasks of the democratic revolution would be realized, the BLPI insisted in its founding documents, only if the working class across South Asia wrested the leadership of the struggle against British colonial rule from the bourgeoisie, mobilized the peasant masses on a revolutionary program against landlordism, and made the anti-imperialist struggle a component part of the socialist struggle of the world working class.

This perspective won powerful support, with the BLPI emerging in the leadership of major working class struggles in Calcutta (Kolkata), Bombay (Mumbai), and Madras (Chennai). The press vilified the BLPI for the leading role it had played in mobilizing workers in Bombay to strike and establish barricades in support of the February 1946 mutiny of Royal Indian Navy (RIN) sailors. Ultimately the RIN rebellion was broken as a result of the combined action of British troops and the Congress and Muslim League leaders’ demands that the mutinous sailors surrender.

Fear of the rising tide of worker-peasant struggles and their impact on the British Indian armed forces caused the Congress to become all the more desperate for a quick settlement with British imperialism.

The destructive impact of Pabloite opportunism

In 1947-48, as Durbo was emerging as a leader of its youth wing, the BLPI took a courageous and principled stand that remains of great contemporary significance. The BLPI opposed British imperialism’s transfer of political power to the national bourgeoisie and the carving out of three “independent” capitalist states in South Asia that have incarnated and fostered communal divisions from their birth. While the Congress and Muslim League oversaw the bloody partition of British India into a Muslim Pakistan and Hindu India, the Sri Lankan bourgeoisie baptized its new state by denying citizenship rights to the “Indian” Tamil plantation workers—who, not incidentally, constituted the most powerful component of the island’s working class.

But rather than deepening this analysis and drawing out for the South Asian and world working class the central lessons of the national bourgeoisie’s abortion of the anti-imperialist struggle, the BLPI’s Indian unit devoted its 1948 congress—the first attended by Durbo—to debating whether to dissolve into the Congress Socialist Party.

Undoubtedly the subsiding of the mass anti-imperialist movement and the popular illusions in the Congress and the new political order in South Asia were powerful factors in the political confusion and disorientation that led to the BLPI’s dissolution. But the proposal to liquidate the BLPI had been resisted for several years by the majority of BLPI leaders and members. Decisive in the political disarming of the BLPI was the opportunist political perspective being developed by Pablo and Mandel, which replaced a unified world revolutionary strategy with a national-tactical orientation toward whatever force presently dominated the working class movement in a given country.

The dissolution of the BLPI had a devastating impact on the development of the Fourth International in South Asia. The Trotskyist movement in India was effectively liquidated. In Ceylon, Pablo encouraged the BLPI unit to merge with a renegade group that had opposed the formation of the BLPI in 1942, stolen the name LSSP for its own organization, and voted for Ceylon’s 1948 independence agreement. The merger of the BLPI with the rival LSSP was a major step in the centrist downsliding of the Sri Lankan Trotskyist movement that culminated in the LSSP joining a bourgeois coalition government led by the Sri Lanka Freedom Party in 1964 and becoming a bulwark of the capitalist order.

Durbo was part of a group in West Bengal, of which Dulal Bose was a principal leader, that vigorously opposed the BLPI’s dissolution. They rebutted those who claimed that joining the Socialist Party of Jaya Prakash Narayan and Ashoka Mehta would bring the Trotskyists “closer to the working class,” by noting that the CSP had functioned as the left-wing of the Congress in its betrayal of the anti-imperialist struggle, was a party of union functionaries and radicalized sections of the middle class, and was rapidly atrophying into an electoral party.

Subsequently Durbo and others in West Bengal who had opposed the BLPI’s dissolution organized themselves around Inqulab (Revolution), formerly the BLPI’s Bengali newspaper. But they were cut off from the struggle within the Fourth International that resulted in the opponents of Pabloite opportunism establishing the International Committee in 1953. They therefore were unable to establish the social roots of the opportunism that had resulted in the BLPI’s liquidation or to clarify the key questions concerning the role of revolutionary leadership and its relationship to the working class involved in refuting the Pabloites’ incantations about the need to integrate into the mass movement.

The leadership of the LSSP, the largest and most politically tested Trotskyist party in Asia, must bear much of the responsibility for the Indian Trotskyists’ ignorance of the ICFI’s opposition to Pabloism. The LSSP leaders opposed many of Pablo’s opportunist formulations, particularly concerning the revolutionary potential of the Soviet Stalinist bureaucracy, but they opposed the decision to rally the genuine Trotskyist elements in a separate organization, fearing that the political rearming of the Fourth International by the International Committee would disrupt their increasingly explicit parliamentary and trade-unionist orientation.

Durbo and the other BLPI comrades who rallied to the IC in the early 1990s always recalled the subsequent four decades with bitterness and shame. In 1954, the Inqulab group fused with the Communist League, the Indian section of the Pabloite international. Under Pabloite influence Durbo and his comrades became increasingly fixated on tactical maneuvers aimed at gaining influence, not clarifying the central political problems facing the working class.

In the mid-1960s, the Inqulab group sought to enter the Communist Party of India (Marxist) or CPM. A split-off from the CPI, the CPM denounced the CPI’s toadying to the Congress party and parroted some Chinese government criticisms of the Soviet leadership, but upheld the entire tradition of Stalinism, from the two-stage theory of revolution and socialism-in-one country to the Moscow trials.

After the CPM leadership refused to allow “counter-revolutionary Trotskyites” to enter their party, Durbo joined the CPM as an individual. However, he quit not long after, when the CPM joined hands with the capitalist state in suppressing the Maoist-Naxalite rebellion.

Political rebirth

“Politically speaking,” Durbo would tell representatives of the SLL and the Socialist Equality Party of Sri Lanka, “I was born again after I met you and other comrades of the ICFI. Because of the persistent and patient efforts of the young ICFI comrades and leaders to explain, discuss and clarify issues I and other comrades from the BLPI who were of an earlier generation were able to overcome the confusion, disillusion and frustration into which Pabloite liquidation had pushed us into for nearly four decades. We feel that we are back in the old and proud BLPI days and the Fourth International of Trotsky. Thanks to the ICFI and its leadership we are happy, clear in our thinking, and confident in the future of our world Trotskyist movement. At last after all these decades we are at peace with our Trotskyist convictions.”

The long years of political confusion and isolation took their toll on Durbo’s health. Had he ever wanted an easy road, the Stalinists in West Bengal, who have led the state government since 1977, would have found him a place in their apparatus, believing his political past and intellectual fortitude would lend them lustre. But Durbo was not open to such blandishments. In 1965 he had been elected the General Secretary of the West Bengal College Teachers Union, but the following year because of his opposition to the unions’ Stalinist leadership he flatly turned down the proposal that he again contest the union elections and instead quit the union.

Because of his political intransigence, Durbo was ostracized by the Stalinists at his workplace and in intellectual circles. He was also subject to police surveillance and his house raided by armed commandos on the claim that he was lending support to the Naxalites. In reality, in his discussion with Maoist-leaning students, Durbo had vigorously opposed the Naxalites’ theories of individual terror and their blood curdling calls for “class annihilation,” that is the murder of local landlords. But he did speak out forcefully against the state’s ruthless repression of the Naxalites and for that he and his family would long suffer police harassment.

By the time he came in contact with representatives of the SLL and the Sri Lankan SEP, physical and emotional strains and stresses had made Durbo an invalid. To keep his asthma at a bay, he had been compelled to depend on a cocktail of medicines, including steroids. He could travel about very little and visits to Kolkata were trying because of the dust and pollution.

But Durbo was rejuvenated by his association with the ICFI. His re-entry into the ranks of the Fourth International coincided with the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the last service rendered by the Soviet bureaucracy to imperialism, the open the turn of the Chinese Stalinist bureaucracy toward capitalist restoration, and the Indian Stalinists’ embrace of the neo-liberal economic reform program of the bourgeoisie. Durbo was eager to do battle with the Stalinist CPM at every level.

“Many people round the Stalinist movement try to justify their support for the politics of the Stalinist party on the ground that the working class is not mature for revolutionary politics,” he commented in one discussion. “But they cover up a decisive fact: that this unpreparedness has been prepared by the politics of the Stalinist party and the Pabloite revisionists who covered up for them.”

Durbo, his wife, Jarana, and daughters, were always pleased to provide accommodation and food to comrades visiting Katwa. In his home town he was renowned for his political knowledge and commitment.

As the WSWS observed in a 2001 obituary for the aforementioned Dulal Bose, his life and that of the other BLPI veterans who rallied to the ICFI in the early 1990s reflected not only the political difficulties that the Trotskyist movement confronted in the post-war period but also the deep roots it had put down in the Indian working class.

A new generation of revolutionary workers, youth and intellectuals in India will draw strength from Durbo’s tenacity, courage and passionate belief in the emancipation of the working class. But above all what he would want them to draw from the vicissitudes of his life are the political lessons that cost him and his generation so much to learn: There are no short-cuts in the protracted struggle for the political independence of the working class; tactics must flow from and be subordinated to a world revolutionary strategy; the Marxist prefers temporary isolation to short-term gains that are purchased at the expense of the political clarification of the working class, because he recognizes that the transformation of the working class into a revolutionary force takes place through the struggle for a political line that articulates its independent, historical interests as a class.

The SLL of India, the SEP of Sri Lanka and the WSWS send their deepest condolences to the family of Comrade Druba Jyoti Majumdar.

On the morning of Sunday, January 16, pioneer Indian Trotskyist Druba Jyoti Majumdar died at his home in Katwa, West Bengal, of asthma. He was 75.

Majumdar, who was known to his family and comrades as Durbo, joined the Bolshevik-Leninist Party of India (BLPI), the then section of the Fourth International in the Indian subcontinent, in 1946 at the age of 17. Throughout the remainder of his life he considered himself a revolutionary socialist and Trotskyist. But Durbo’s political development was cut off for decades by the dissolution of the BLPI’s Indian unit into the petty bourgeois Congress Socialist Party in 1948.

Not

until the early 1990s did Durbo and a group of Kolkata (Calcutta)

socialists with whom he was associated—most of them BLPI veterans—learn

of the decades-long struggle that the International Committee of the

Fourth International (ICFI) had waged against Pabloism, a virulent

opportunist tendency that arose within the Fourth International under

the pressure of the post-World War II restabilization of capitalism. Led

by Michel Pablo and Ernest Mandel, this tendency claimed that objective

forces would compel the Soviet Stalinist bureaucracy, its satellite

parties, the social-democrats, and, in the countries oppressed by

imperialism, the national bourgeoisie, to play a progressive and even

revolutionary role. The task of Trotsykists, therefore, was not to wrest

the leadership of the working class from these alien class forces, but

to pressure them to the left.

Not

until the early 1990s did Durbo and a group of Kolkata (Calcutta)

socialists with whom he was associated—most of them BLPI veterans—learn

of the decades-long struggle that the International Committee of the

Fourth International (ICFI) had waged against Pabloism, a virulent

opportunist tendency that arose within the Fourth International under

the pressure of the post-World War II restabilization of capitalism. Led

by Michel Pablo and Ernest Mandel, this tendency claimed that objective

forces would compel the Soviet Stalinist bureaucracy, its satellite

parties, the social-democrats, and, in the countries oppressed by

imperialism, the national bourgeoisie, to play a progressive and even

revolutionary role. The task of Trotsykists, therefore, was not to wrest

the leadership of the working class from these alien class forces, but

to pressure them to the left.

The ICFI’s critique of Pabloism shed an entirely new light on the BLPI’s dissolution—for which Pablo had pressed—and on the bitter political experiences that the members of the Kolkata group had subsequently made as supporters of the Pabloites’ international organization, now known as the United Secretariat. After extensive discussions with ICFI representatives, the Calcutta group, including Durbo, Dulal Bose, Ganesh Dutta, Nirmal Samajpathi and Dinesh Sanyal, joined the Socialist Labour League, the Indian organization in political solidarity with the ICFI.

Alongside Dulal Bose, Durbo henceforth played a leading role in developing the SLL’s work in West Bengal, the principal bastion of the Stalinist Communist Party of India (Marxist). Although hobbled by asthma, he wrote extensively for the SLL’s Bengali newspaper Anthrajathik Shramik (International Worker) and its predecessor Shramiker Path (Workers’ Path), addressed public meetings of the SLL in Katwa and Kolkata, made many Bengali translations of articles published on the World Socialist Web Site, and collaborated in preparing the Bengali-language edition of David North’s The Heritage We Defend: A Contribution to the History of the Fourth International.

A philosophy professor at Katwa College, Durbo had a keen mind and wide-ranging intellectual interests. He had studied the Marxist classics and both ancient and modern Indian philosophy. Fluent in Bengali, Hindi and English, he was an amateur philologist. When comrades visited from other parts of India or abroad he would delight in discussing and discovering the relations between words in different languages, including links between Sinhalese and Bengali.

Durbo made an exhaustive study of psychology and sought to illuminate psychological problems from a materialist perspective in the Bengali journal Manabman (Human Mind) and a two-volume work published in 2003-04, Manabik Chetanar Sawrup Sandhane (In Search of Human Consciousness). The West Bengal government has published his pioneering English-Bengali dictionary of Abnormal Psychology and Psychopathology.

Till the end of his days Durbo retained a boyish spirit. Although his asthma made it very difficult for him to travel, he was ever eager to contribute to the work of the Socialist Labour League. His concern for his fellow comrades’ health and well-being was testament to his generous spirit and to his understanding of the demands placed on, and the vital importance of, revolutionary cadres.

Durbo and the BLPI

Durbo was born on March 3, 1929 in Bapna, in the Rangpur district of present day Bangladesh. The second of five children, he came from a privileged Brahmin family. His father was a Deputy Magistrate entrusted with doling out British imperialist justice.

Under the influence of India’s mass anti-imperialist movement, the mounting struggles of the working class, and the horrors of fascism, world war, and the British-provoked Bengal Famine of 1943-44, Durbo rebelled against his upbringing. At the age of thirteen he participated in the Quit India movement, the spontaneous nationwide rebellion that erupted after the August 1942 arrest of senior Congress leaders.

Around this time Durbo cut off his “holy” thread, the symbol of a male Brahmin’s religious observance and caste superiority. Later he would defy the Indian tradition of arranged marriages.

Durbo first came into contact with the BLPI in 1947 in Calcutta, where he was studying economics at Presidency College. The two years between the end of World War II and the dissolution of Britain’s Indian empire were filled with momentous struggles of an incipient revolutionary character, including strikes, peasant rebellions, anti-feudal movements in the princely states, and mass demonstrations against the incarceration of members of Subhas Chandra Bose’s Indian National Army. Although India and Bengal were to be partitioned along communal lines in August 1947, these struggles invariably united Hindus, Muslims, Sikhs and Christians.

Durbo, as a result of his reading and study of events, had by this point already decided to become a Marxist. He well recognized the bourgeois character of the Indian National Congress. Under Gandhi’s leadership, the Congress mounted controlled mass mobilizations in order to pressure India’s colonial overlords to relinquish control over the state apparatus, while adamantly opposing any independent action of the working class or challenge to capitalist property.

Durbo had also taken the measure of the Stalinist Communist Party of India. In the name of defending the Soviet Union, the CPI had openly allied itself with the British colonial regime from the beginning of 1942 through the end of World War II, and it condemned and agitated against the Quit India uprising. During the semi-insurrectionary struggles of 1945-47, the CPI subordinated the working class to the rival parties of the national bourgeoisie, calling on workers to press the Congress and the Muslim League—whose leaders had daggers drawn against each other—to recognize their “responsibility” to combine and lead an anti-British National Front.

For a time in the mid-1940s, Durbo considered himself a follower of the Congress Socialist Party (CSP), which had played a leading role in the Quit India rebellion. A faction of the Congress, the CSP sought to combine Gandhianism with Fabianism and Marxism. By 1947, Durbo had grown troubled by the CSP’s acquiescence before the Congress leaders’ drive for a settlement with British imperialism, under which the Congress would take control of the colonial state machine.

Against the Congress, the radical nationalists of the CSP, and the Stalinists, the BLPI alone advanced a revolutionary perspective.

Founded in 1942 on the initiative of the Lanka Sama Samaja Party of Ceylon (Sri Lanka), the BLPI united Trotskyists in all parts of British and princely India and Ceylon.

The development of a pan-Indian revolutionary working class party was a strategy flowing from the LSSP’s adherence to the Fourth International and attempt to develop the program of permanent revolution. The tasks of the democratic revolution would be realized, the BLPI insisted in its founding documents, only if the working class across South Asia wrested the leadership of the struggle against British colonial rule from the bourgeoisie, mobilized the peasant masses on a revolutionary program against landlordism, and made the anti-imperialist struggle a component part of the socialist struggle of the world working class.

This perspective won powerful support, with the BLPI emerging in the leadership of major working class struggles in Calcutta (Kolkata), Bombay (Mumbai), and Madras (Chennai). The press vilified the BLPI for the leading role it had played in mobilizing workers in Bombay to strike and establish barricades in support of the February 1946 mutiny of Royal Indian Navy (RIN) sailors. Ultimately the RIN rebellion was broken as a result of the combined action of British troops and the Congress and Muslim League leaders’ demands that the mutinous sailors surrender.

Fear of the rising tide of worker-peasant struggles and their impact on the British Indian armed forces caused the Congress to become all the more desperate for a quick settlement with British imperialism.

The destructive impact of Pabloite opportunism

In 1947-48, as Durbo was emerging as a leader of its youth wing, the BLPI took a courageous and principled stand that remains of great contemporary significance. The BLPI opposed British imperialism’s transfer of political power to the national bourgeoisie and the carving out of three “independent” capitalist states in South Asia that have incarnated and fostered communal divisions from their birth. While the Congress and Muslim League oversaw the bloody partition of British India into a Muslim Pakistan and Hindu India, the Sri Lankan bourgeoisie baptized its new state by denying citizenship rights to the “Indian” Tamil plantation workers—who, not incidentally, constituted the most powerful component of the island’s working class.

But rather than deepening this analysis and drawing out for the South Asian and world working class the central lessons of the national bourgeoisie’s abortion of the anti-imperialist struggle, the BLPI’s Indian unit devoted its 1948 congress—the first attended by Durbo—to debating whether to dissolve into the Congress Socialist Party.

Undoubtedly the subsiding of the mass anti-imperialist movement and the popular illusions in the Congress and the new political order in South Asia were powerful factors in the political confusion and disorientation that led to the BLPI’s dissolution. But the proposal to liquidate the BLPI had been resisted for several years by the majority of BLPI leaders and members. Decisive in the political disarming of the BLPI was the opportunist political perspective being developed by Pablo and Mandel, which replaced a unified world revolutionary strategy with a national-tactical orientation toward whatever force presently dominated the working class movement in a given country.

The dissolution of the BLPI had a devastating impact on the development of the Fourth International in South Asia. The Trotskyist movement in India was effectively liquidated. In Ceylon, Pablo encouraged the BLPI unit to merge with a renegade group that had opposed the formation of the BLPI in 1942, stolen the name LSSP for its own organization, and voted for Ceylon’s 1948 independence agreement. The merger of the BLPI with the rival LSSP was a major step in the centrist downsliding of the Sri Lankan Trotskyist movement that culminated in the LSSP joining a bourgeois coalition government led by the Sri Lanka Freedom Party in 1964 and becoming a bulwark of the capitalist order.

Durbo was part of a group in West Bengal, of which Dulal Bose was a principal leader, that vigorously opposed the BLPI’s dissolution. They rebutted those who claimed that joining the Socialist Party of Jaya Prakash Narayan and Ashoka Mehta would bring the Trotskyists “closer to the working class,” by noting that the CSP had functioned as the left-wing of the Congress in its betrayal of the anti-imperialist struggle, was a party of union functionaries and radicalized sections of the middle class, and was rapidly atrophying into an electoral party.

Subsequently Durbo and others in West Bengal who had opposed the BLPI’s dissolution organized themselves around Inqulab (Revolution), formerly the BLPI’s Bengali newspaper. But they were cut off from the struggle within the Fourth International that resulted in the opponents of Pabloite opportunism establishing the International Committee in 1953. They therefore were unable to establish the social roots of the opportunism that had resulted in the BLPI’s liquidation or to clarify the key questions concerning the role of revolutionary leadership and its relationship to the working class involved in refuting the Pabloites’ incantations about the need to integrate into the mass movement.

The leadership of the LSSP, the largest and most politically tested Trotskyist party in Asia, must bear much of the responsibility for the Indian Trotskyists’ ignorance of the ICFI’s opposition to Pabloism. The LSSP leaders opposed many of Pablo’s opportunist formulations, particularly concerning the revolutionary potential of the Soviet Stalinist bureaucracy, but they opposed the decision to rally the genuine Trotskyist elements in a separate organization, fearing that the political rearming of the Fourth International by the International Committee would disrupt their increasingly explicit parliamentary and trade-unionist orientation.

Durbo and the other BLPI comrades who rallied to the IC in the early 1990s always recalled the subsequent four decades with bitterness and shame. In 1954, the Inqulab group fused with the Communist League, the Indian section of the Pabloite international. Under Pabloite influence Durbo and his comrades became increasingly fixated on tactical maneuvers aimed at gaining influence, not clarifying the central political problems facing the working class.

In the mid-1960s, the Inqulab group sought to enter the Communist Party of India (Marxist) or CPM. A split-off from the CPI, the CPM denounced the CPI’s toadying to the Congress party and parroted some Chinese government criticisms of the Soviet leadership, but upheld the entire tradition of Stalinism, from the two-stage theory of revolution and socialism-in-one country to the Moscow trials.

After the CPM leadership refused to allow “counter-revolutionary Trotskyites” to enter their party, Durbo joined the CPM as an individual. However, he quit not long after, when the CPM joined hands with the capitalist state in suppressing the Maoist-Naxalite rebellion.

Political rebirth

“Politically speaking,” Durbo would tell representatives of the SLL and the Socialist Equality Party of Sri Lanka, “I was born again after I met you and other comrades of the ICFI. Because of the persistent and patient efforts of the young ICFI comrades and leaders to explain, discuss and clarify issues I and other comrades from the BLPI who were of an earlier generation were able to overcome the confusion, disillusion and frustration into which Pabloite liquidation had pushed us into for nearly four decades. We feel that we are back in the old and proud BLPI days and the Fourth International of Trotsky. Thanks to the ICFI and its leadership we are happy, clear in our thinking, and confident in the future of our world Trotskyist movement. At last after all these decades we are at peace with our Trotskyist convictions.”

The long years of political confusion and isolation took their toll on Durbo’s health. Had he ever wanted an easy road, the Stalinists in West Bengal, who have led the state government since 1977, would have found him a place in their apparatus, believing his political past and intellectual fortitude would lend them lustre. But Durbo was not open to such blandishments. In 1965 he had been elected the General Secretary of the West Bengal College Teachers Union, but the following year because of his opposition to the unions’ Stalinist leadership he flatly turned down the proposal that he again contest the union elections and instead quit the union.

Because of his political intransigence, Durbo was ostracized by the Stalinists at his workplace and in intellectual circles. He was also subject to police surveillance and his house raided by armed commandos on the claim that he was lending support to the Naxalites. In reality, in his discussion with Maoist-leaning students, Durbo had vigorously opposed the Naxalites’ theories of individual terror and their blood curdling calls for “class annihilation,” that is the murder of local landlords. But he did speak out forcefully against the state’s ruthless repression of the Naxalites and for that he and his family would long suffer police harassment.

By the time he came in contact with representatives of the SLL and the Sri Lankan SEP, physical and emotional strains and stresses had made Durbo an invalid. To keep his asthma at a bay, he had been compelled to depend on a cocktail of medicines, including steroids. He could travel about very little and visits to Kolkata were trying because of the dust and pollution.

But Durbo was rejuvenated by his association with the ICFI. His re-entry into the ranks of the Fourth International coincided with the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the last service rendered by the Soviet bureaucracy to imperialism, the open the turn of the Chinese Stalinist bureaucracy toward capitalist restoration, and the Indian Stalinists’ embrace of the neo-liberal economic reform program of the bourgeoisie. Durbo was eager to do battle with the Stalinist CPM at every level.

“Many people round the Stalinist movement try to justify their support for the politics of the Stalinist party on the ground that the working class is not mature for revolutionary politics,” he commented in one discussion. “But they cover up a decisive fact: that this unpreparedness has been prepared by the politics of the Stalinist party and the Pabloite revisionists who covered up for them.”

Durbo, his wife, Jarana, and daughters, were always pleased to provide accommodation and food to comrades visiting Katwa. In his home town he was renowned for his political knowledge and commitment.

As the WSWS observed in a 2001 obituary for the aforementioned Dulal Bose, his life and that of the other BLPI veterans who rallied to the ICFI in the early 1990s reflected not only the political difficulties that the Trotskyist movement confronted in the post-war period but also the deep roots it had put down in the Indian working class.

A new generation of revolutionary workers, youth and intellectuals in India will draw strength from Durbo’s tenacity, courage and passionate belief in the emancipation of the working class. But above all what he would want them to draw from the vicissitudes of his life are the political lessons that cost him and his generation so much to learn: There are no short-cuts in the protracted struggle for the political independence of the working class; tactics must flow from and be subordinated to a world revolutionary strategy; the Marxist prefers temporary isolation to short-term gains that are purchased at the expense of the political clarification of the working class, because he recognizes that the transformation of the working class into a revolutionary force takes place through the struggle for a political line that articulates its independent, historical interests as a class.

The SLL of India, the SEP of Sri Lanka and the WSWS send their deepest condolences to the family of Comrade Druba Jyoti Majumdar.

Source:

Druba Jyoti Majumdar: pioneer Indian Trotskyist dies

By Nanda Wickremasinghe and Ganesh Dev

By Nanda Wickremasinghe and Ganesh Dev